This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Caro Meets Theatre Interview

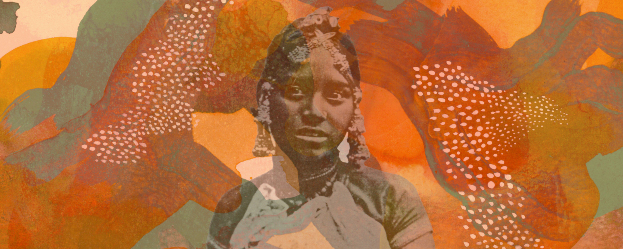

Michael Walling: The Great Experiment

By Caro Moses | Published on Friday 31 January 2020

You’re no doubt aware of Border Crossings, a theatre company that’s been producing excellent and important work for the last twenty five years. So you’ll no doubt be pleased to hear that their latest show, ‘The Great Experiment’, will be touring London venues this month.

The play is focused on the post-slavery practice of indentured labour and its effects. To find out more I spoke to the director of the piece, company founder Michael Walling.

CM: Can you start by telling us about the story the play tells? What is the show about?

MW: On one level it’s a very simple story about an unnamed young man from Bihar in Northern India in the 1840s, who is recruited to travel to Mauritius as an indentured labourer. But it’s also a play about modern London: we see the actors as themselves, asking how they can relate to this history, how to make sense of it, how to live with the way it’s shaped our city and our world.

CM: For anyone not familiar with it, can you explain the concept of indentured labour?

MW: When slavery was abolished in the British Empire, the people who ran the sugar industry had a problem: who was going to work the plantations? The former slaves didn’t want to… And so they turned to India as a source of cheap labour. The indenture itself was a five-year contract by which an Indian worker would agree to be transported and to work incredibly long hours, in return for food, board, and meagre wages. What’s really striking is that so many were willing to do this, and that they were even able to send or take money back to their families in India. You could say that it was a very successful system… It lasted until the 1920s.

CM: How is the play structured?

MW: There are some scenes set in the historical past, and these are deliberately presented in quite a stylised way. These alternate with scenes set in our own rehearsal room, and in the actors’ lives beyond the room, which are much more realistic and gritty. It’s a way of pushing two different realities up against each other. The indentured labourers become like ghosts – haunting our contemporary lives. Questioning us.

CM: What wider themes does the play explore?

MW: It goes into a lot of the big questions we’re facing in London right now. Some of them are quite specific to us as theatre-artists: who should be telling the stories of people from migrant backgrounds, what role white British people might take in the emerging intercultural dialogue, things like that. And others expand from that into a much bigger picture – the whole question of how people from different backgrounds think of themselves, and each other; the question of why some communities are so much wealthier than others; big enduring issues like inherited shame and white privilege…

CM: What research did you do on the topic before creating the play?

MW: I first had the idea for the play on a visit to Mauritius, when I saw the Apravaasi Ghat – the place where the indentured workers landed. That was really moving. Then we worked closely with a historical research project, which meant we had three different professional historians coming into our devising room to discuss the subject with us.

It was such a luxury… Marina Carter knows more about Mauritian history than anybody, and she found a whole series of amazing personal stories that we were able to use. Then, Andrea Major helped us to put it in the context of the Empire, and Crispin Bates guided us through the Indian background.

CM: Can you talk us through the stages of creating the play? How did the devising process work?

MW: We started from the research and dialogues with the historians. We looked for ways in which we could tell some of the personal stories Marina told us, and dramatise the background we were getting from Andrea and Crispin. It actually proved really difficult – the stories of the indentured labourers and slaves were so distant from our own experience that they proved impossible to improvise.

At the same time, we were having lots of discussions about how the history made us feel, and about how we could locate ourselves within it. Given the differing backgrounds of the cast, that was a complex process.

I started to jot down interesting things that people were saying, and using them as ways in to creating a different sort of drama – something rooted in our growing sense that our own lives in 21st Century London had actually been shaped by this history. That’s really organic, because there are lots of overlaps between the “characters” and ourselves. It’s a very delicate process, and one that is ongoing.

CM: Can you tell us a bit about the creative team?

MW: Shiraz Bayjoo, our designer, is a Mauritian fine artist. He’s been obsessed with the history for a long time, and has an extraordinary archive of images that he can draw off to create a visual context for the scenes set in the past. He was really active during the devising process, and not just in terms of visual ideas.

Maria da Luz Ghoumrassi, our Movement Director, is another islander – she’s from Cape Verde, and Assistant Director Carlota Arencibia is from the Canaries. I wanted to work with people who would find some kind of personal link to the history. In case of the Lighting Designer, Catherine Webb, it was to do with a novel she wrote that tackles the theme of colonialism. I’m interested in artists who offer a range of approaches, and who have a personal link to the material as well as professional skills.

CM: What made you want to tackle this subject?

MW: I directed three plays in Mauritius in the 90s – that’s how I met my wife, Nisha Dassyne, and in many ways this play is hers. She’s performing in it, and it tackles her family story. But it’s also a bigger, more political subject: the history of indentured migration needs to be told at a time when Britain is increasingly cutting itself off from a wider world, retreating into a myth of exceptionalism and a resurgent imperialism… The Hostile Environment, the Windrush scandal, the Brexit vote – there’s a painful sense of migrants being rejected and demonised, and I felt an urgent need to question that.

CM: Is there an aim to educate? It seems like this is isn’t widely known about – why do you think that is?

MW: In a way, yes – though the play isn’t a history lesson. It’s actually very funny, even though it deals with some of these difficult issues.

You’re quite right that the story isn’t widely known. My hunch is that’s because it’s not a narrative that can easily be absorbed into the positive story British society likes to tell about itself. We talk about slavery because we can talk about its abolition, and we can talk about Wilberforce and Equiano. Indenture rather messes up the ‘feel-good’ factor: it turns out that the Empire carried on relying on the incredibly cheap labour of people from the colonies, long after slavery. In many ways, it still does.

CM: Aside from the show, are there other events happening alongside?

MW: There are some great panels lined up to talk after several of the shows, with people like Samita Sen from Cambridge University, Catherine Hall who led the creation of the UCL website on British slave ownership, Mauritian writers like Roshni Mooneeram and Gitandjeli Pyndiah, and the Guyanese writer Lainy Malkani.

We’re also running a Collection Day at the National Maritime Museum on 29 Feb: a chance for people with indentured heritage to bring their own family histories and objects for discussion with the experts. We love collecting oral histories from sources outside the historical mainstream – it gives a whole new perspective on what our world is all about!

CM: Can you tell us a bit about Border Crossings, its history, and how it came to be?

MW: I set the company up in response to some directing work I did in America and India in the 90s. It became very apparent to me that we had to find new ways of talking to one another: I felt that theatre could become an experimental space where we could explore how the globalised world might be jointly inhabited. It felt very urgent then – and it feels even more urgent now.

CM: What aims does it have for the future?

MW: We need to fight to retain our international links in the face of the walls that are being put up everywhere. We need to work with people who think and live differently from ourselves. We need to understand ourselves better by seeing ourselves through the eyes of others.

CM: What’s coming up next for the company?

MW: We’ve just set up a new community theatre group for young refugees and their non-refugee peers. We’ve called it ‘Border Crossers’. They’ll be doing their first show in the autumn. We’re also working with the British Museum to curate some indigenous performances alongside their Arctic exhibition, with a strong emphasis on environmental issues. We’re making a film about working across or without languages… And there are a couple of new plays in the early stages of development… Quite busy, really…!

‘The Great Experiment’ tours London venues throughout most of February, calling at Enfield’s Dugdale Centre from 6-7 Feb, Tara Theatre from 11-15 Feb, the Playground Theatre from 18-19 Feb, Cutty Sark from 21-22 Feb, and the Museum Of London Docklands on 23 Feb. More info on all dates here.

LINKS: www.bordercrossings.org.uk | twitter.com/BorderCrossings